Sabbadānaṃ dhammadānaṃ jināti

Tipiṭaka(Mūla) / Suttapiṭaka / Khuddakanikāya / Dhammapadapāḷi

The gift of Dhamma excels all other gifts.

Style One:A Popular method ,whose foundations of practice are used at many meditation centres throughout Thailand

On the Path to Nibbāna

[a slightly abridged revision of a book by the most Ven.Dr.[Jao Khun] Tong Sirimangalo 1996/B.E.2539 ]

ISBN: 974-89447-5-1I

Introduction

Theory

How Buddhism Stands Out

Samatha versus Vipassana Meditation

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

Virtue, Concentration, Wisdom (Sila, Samadhi, Pañña)

The Six Fields of Insight (Vipassana Bhumi)

Defilements of Insight (Vipassanukilesa)

Cutting Off the Roots of Vatta (the Cycle of Rebirth)

Important Principles in the Practice

The Three Characteristics of Existence (Tilakkhana)

Entering into the Knowledge of the Path (Magga-Ñana)

Defilements that are Responsible for the Impurity of the Human Mind

The Mind of the Noble Ones

Practicing the Dhamma in the Higher Stages

Odds and Ends

Practice

Opening Ceremony (Receiving the Meditation)

Advice to Meditators: Guidelines for the Practice

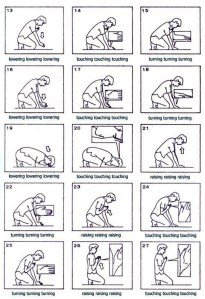

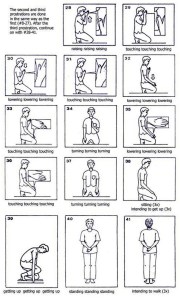

Mindful (Satipatthana) Prostration HOWTO

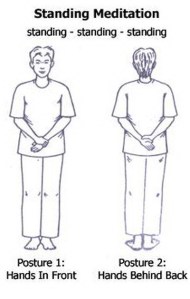

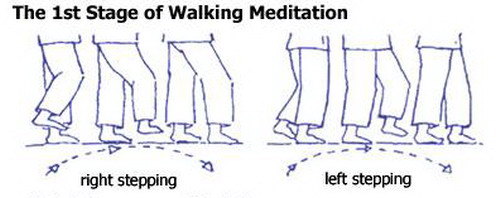

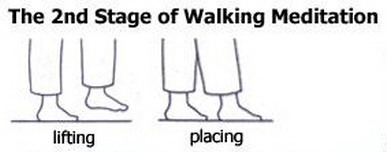

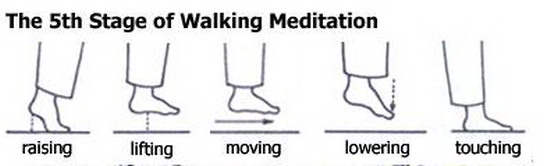

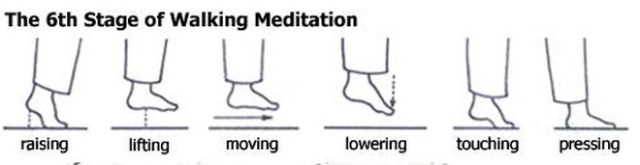

Walking Meditation HOWTO

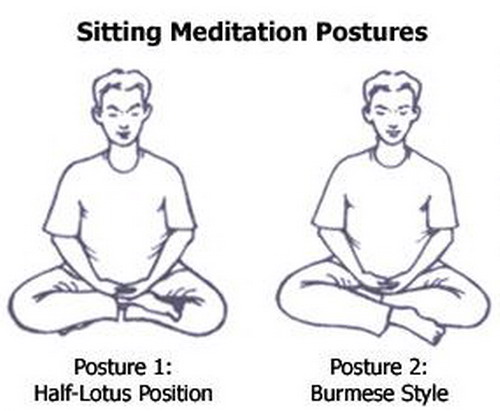

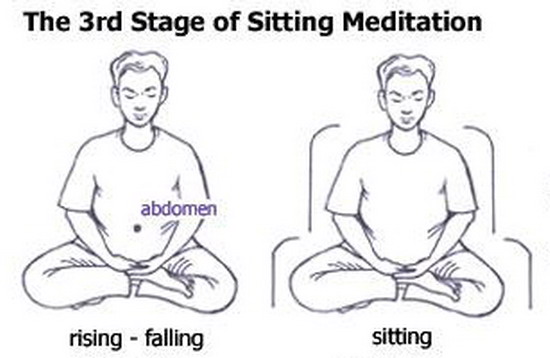

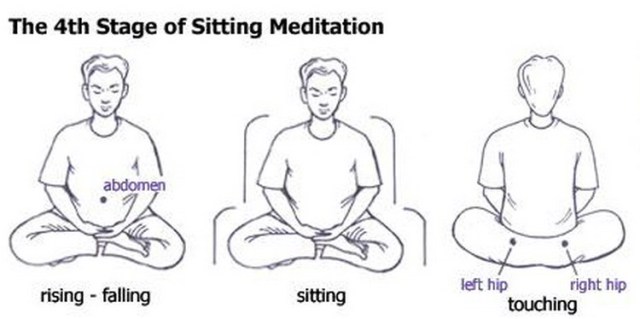

Sitting Meditation HOWTO

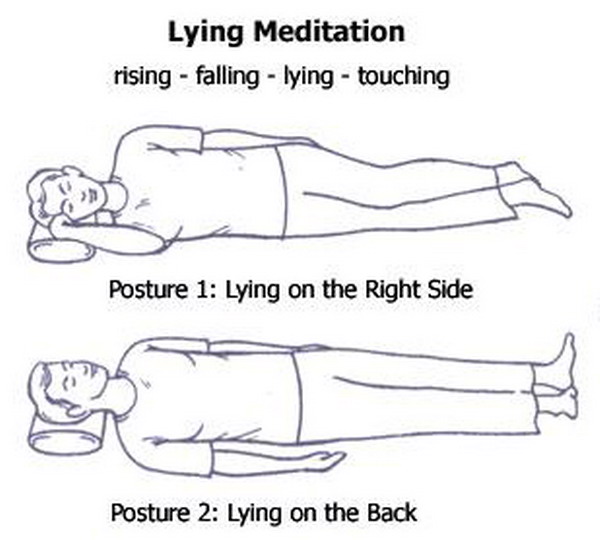

Lying Meditation

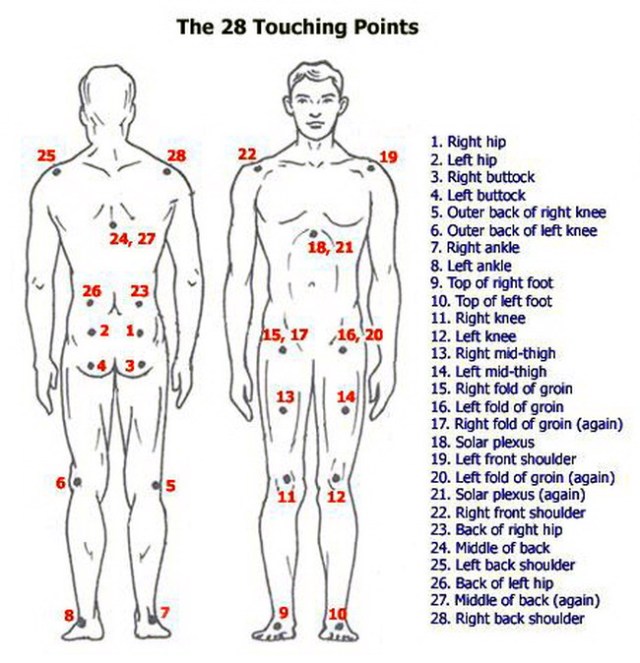

Changing the Touching Points

Steps in the Practice

Steps in Reviewing the Knowledges (Ñana)

Closing Ceremony

Conclusion

Yo vo, ānanda, mayā dhammo ca vinayo ca desito paññatto, so vo mamaccayena satthā’ti (dī. ni. 2.216).

What I have taught and laid down, Ananda, as doctrine and discipline (Dhamma-Vinaya),

let them be your teacher when I am gone.

Preface

Natthi pañña sama abha.

There is no light that compares to wisdom.

People on earth consider the sunlight and the moonlight to be bright lights in the world. But our Lord Buddha has said that wisdom and knowledge (paññañana) is a light brighter than that of the sun and the moon. Why is this? Because this outer light, that is, the sunlight and the moonlight, can’t shine into hidden places. The light of wisdom and knowledge, however, can shine into hidden places.

Therefore, the light of wisdom and knowledge is the light most sublime in the world. There are three types of wisdom: wisdom born of learning (sutamaya-pañña), wisdom born of reflection (cintamaya-pañña) and wisdom born of meditation (bhavanamaya-pañña). The wisdom born of learning and of reflection are the Dhamma that will only help you make it in the world. The wisdom born of meditation, on the other hand, will free the mind from all suffering.

As a consequence, the light of wisdom and knowledge that arises from the practice of vipassana meditation in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness on whose path the Buddha and all his disciples have followed in order to realize the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, this path is none other than the four foundations of mindfulness.

I rejoice in the merit of all my disciples who have helped one another to perform this wholesome deed. May each and every disciple be blessed with happiness and success.

Phra Rajabrahmacariya (Venerable Ajahn Tong)

Abbot and Director of the Vipassana Center

Wat Phradhatu Sri Chom Tong Voravihara

Ban Luang, Chom Tong, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Introduction

The more agitated the world becomes, the more those who see danger in samsara (the rounds of rebirth) hurry to find their way to the shade of the Gotama tree, because it is the shade of tranquility and coolness that was created by the Lord Buddha for all beings.

Not Even the Wealth of All the Three Worlds Can Compare

Pathabyā ekarajjena, saggassa gamanena vā

Sabbalokādhipaccena, sotāpattiphalaṃ varaṃ.

Tipiṭaka(Mūla) / Suttapiṭaka / Khuddakanikāya / Dhammapadapāḷi

Not the king who is complete with great wealth and free among humans, nor Sakka, the King of the Devas, with power over the 6 heavenly abodes, nor Maha Brahma with great psychic powers among the Brahmas, can compare with the stream-enterer.

Worldly Taste versus the Taste of the Dhamma

The more we partake of the worldly taste, the more tasteless it becomes. It is like eating sugar cane from the bottom up. The more we partake of the taste of the Dhamma, the sweeter it becomes. It is like eating sugar cane from the top down.

The mind that is satisfied with the taste of the Dhamma finds no meaning in worldly happiness. There are many worldly tastes but there is only one taste of the Dhamma—vimuttirasa, the taste of liberation.

Sabbarasaṃ dhammaraso jināti.

The taste of the Dhamma excels all other tastes.

Tipiṭaka(Mūla) / Suttapiṭaka / Khuddakanikāya / Dhammapadapāḷi

Bonds

Putto give dhanam pade bhariya hatthe.

A child is like a bond around the neck.

Wealth is like a bond around the feet.

A spouse is like a bond around the wrists.

Once these three bonds are secured, they are hard to break. They are bonds tied only loosely but are hard to undo. Bonds made up of rope, leather, wood and iron are not as strong as the bond of sense desires (kama).

The world (i.e., beings) is subject to decay. It is impermanent.

All beings have nothing to protect them.

They don’t have control over themselves.

All beings have nothing that belongs to them.

They must leave everything behind and go.

All beings are always lacking.

They know not enough and thus are slaves to craving.

Before the sun rises in the sky, golden and silver rays must first appear.

Likewise, before the dawn of the noble path, virtue (sila) must first appear.

‘‘ 106. ‘‘Ekāyano ayaṃ, bhikkhave, maggo sattānaṃ visuddhiyā, sokaparidevānaṃ [pariddavānaṃ (sī. pī.)] samatikkamāya, dukkhadomanassānaṃ atthaṅgamāya, ñāyassa adhigamāya, nibbānassa sacchikiriyāya, yadidaṃ cattāro satipaṭṭhānā. ’’ ti (dī. ni. 2.373).

This is the only way, bhikkhus, for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the destruction of physical and mental suffering, for reaching the right path, for the realization of Nirvana, namely, the four foundations of mindfulness.

Have you ever asked yourself, “What is the real purpose of life?”

As long as you still can’t answer this question, you will have to live life pointlessly and with hesitation, like one who walks in darkness who can’t see even the danger right in front of them, like a bird that flies in circles in the middle of an ocean, unable to find land.

Why were we born?

We weren’t born to merely search for enjoyment with each passing day. We weren’t born to become intoxicated with delicious worldly tastes, that is, with food, lust and honor. We weren’t born to become slaves to life. We weren’t born merely to study, work, settle down, get a family, have children and then become old, sick and then die.

If we were born for these things, then it would mean that we were only born to cycle in samsara, to be prey to worms and are unable to be freed from this world. Any amount of money would be meaningless.

But we were born to be released from the chains and fetters which bind our mind, in order to be free. We were born to free ourselves from the power and dominance of defilements, of craving. We were born to improve our life and consciousness, developing it to the highest possible level, which is the purification of our mind and the crossing of the land of darkness of life, in order to reach the end of life, that is, the end of suffering, Nirvana.

The Buddha’s Words

Nirvana exists.

The path to Nirvana exists.

I, the pointer of the path to Nirvana, exist.

If you don’t walk the path, then how will you realize Nirvana?

The nature that calms the mind suppressing the hindrances is called “samatha (calm) meditation.”

The nature that gives rise to clear understanding of the states of dhamma, that is of rupa and nama, as being impermanent, suffering and non-self, is called “vipassana (insight) meditation.”

Nirvana

“Ananda, you can’t use only knowledge and ignorance to be the measurement. You have to take the ability to abandon defilements to be the measurement, because those who will realize Nirvana can do so only by depending on the abandoning of defilements. Once the defilements have been abandoned, then Nirvana will be realized.”

Typical Characteristics of All Noble Ones

They do things that others find hard to do.

They endure through what others find hard to endure through.

They conquer what others find hard to conquer.

They, therefore, achieve what all others find hard to achieve.

Lokiyajana are those not freed from the world, searching for things that exist and staying with things that exist. Lokuttarajana are those beyond the world, searching for things that don’t exist and staying with things that don’t exist.

“Rahula, make your mind like the earth. Because if you constantly make your mind like the earth, then neither the pleasant nor the unpleasant mind-objects that come into contact with the mind, can make it waver. It’s like how people sometimes throw clean things sometimes dirty things onto the earth, or how they sometimes urinate or defecate or spit onto the earth, the earth knows not anger, becomes not offended nor annoyed; nor will it feel oppressed or become weary or disgusted with those things. Rahula, if you constantly make your mind like the earth in this way, no mind-objects will be able to overpower your mind.”

Theory

Our world today is filled with unrest, chaos and confusion. We are unable to escape from unwholesome things that have always been there. We are unable to get away from looking down at others, from jealousy, oppression, betrayal, exploitation, deceit, quarrels and murder. These things will probably still exist among human beings in general. All these unskillful things weren’t created by nature, but by human beings themselves. Teachers of the various faiths and religions have all tried to find and establish a foundation so that by doing good and refraining from evil, human beings may create peace and happiness for the world.

The Lord Buddha, who is the teacher of the Buddhist religion, also did the same. But besides teaching human beings to do good and to refrain from evil, the Buddha also taught us to purify the mind, which is recorded in one of his teachings known as “OvadaPatimokkha”:

‘‘ Sabbapāpassa akaraṇaṃ, kusalassa upasampadā;

Sacittapariyodāpanaṃ [pariyodapanaṃ (sī.) dha. pa. 183; dī. ni. 2.90 passitabbaṃ], etaṃ buddhāna sāsana ’’ nti.

To refrain from all evil; To cultivate good; To purify the mind:

This is the teachings of all the Buddhas.

How Buddhism Stands Out

The method by which the mind can be purified doesn’t exist in any other religions in the world; it only exists in the Buddhist religion. According to Buddhism, every human mind by nature is impure, being cluttered by defilements which taint the mind; these defilements consist of greed, hatred and delusion. And it is precisely due to greed, hatred and delusion that human beings commit all kinds of unwholesome deeds.

We have probably already seen all too many times that people who otherwise seem incapable of anger can at times become so angry that they kill another person without being conscious of it. Or some people who are very honest and upright can one day end up embezzling a great amount of wealth. Or sometimes, a person respected and admired by many people becomes one engaging in shameful and immoral behavior as a result of delusion.

These things shouldn’t happen but they have already happened and in large numbers, and they shall continue to increase.

That things are this way is because greed, hatred and delusion are disturbances, like three fires within us. As long as there is no fuel, the fires won’t flare up. But once there is right fuel, the fires will immediately blaze up. The study, the training or the mind’s nature are not able to do anything about it. This is because greed, hatred and delusion have greater strength.

Although teaching people to do good and to refrain from evil can bring people to practice accordingly, it has no power to have people practice that way indefinitely. Because the human mind is impure and cluttered by defilements within. Once they come across an appropriate bait, then they will have to do evil once again. As a result, evil have existed up to the present day, and will generally prevail in the world.

For this reason, the Buddha say that in order for human beings to truly give up evil, they must first purify their mind, to free the mind from defilements. Once their mind has become purified, they won’t perform any more unwholesome deeds but will only do good, as the roots that cause unwholesome actions—that is, the defilements—have been destroyed. Therefore, the mind is a priceless treasure that belongs to human beings.

Samatha versus Vipassana Meditation

The method of mind purification as taught by the Buddha is what is known as meditation. There are two types of meditation in Buddhism: samatha (calm) meditation and vipassana (insight) meditation. These two types of meditation differ both in their method of practice and in the results they yield. That is, samatha meditation aims at mundane (lokiya) peace by going for the jhanas in order to obtain mundane supernatural powers (lokiya abhiñña). It has the Brahma world as its highest destination. Vipassana meditation, on the other hand, aims at supramundane (lokuttara) peace, which is the peace that is freed from the world. It has Nirvana as its highest destination.

Samatha meditation takes a concept (paññatti) as its object of meditation; that is, it takes for its object of meditation the things that the world supposes and labels to be this and that, like, for example, the 10 kasinas. Vipassana meditation, in contrast, takes ultimate reality (paramattha) as its object of meditation; that is, it concentrates on rupa and nama or the five aggregates which are true and real.

In practicing samatha meditation, one needs to consider one’s predominant temperament. For example, those with a predominantly lustful temperament (raga-carita) should develop meditation on the foulness of the body (asubha). Those with a predominantly hateful temperament (dosa-carita) should develop loving-kindness meditation. Those with a predominantly deluded temperament (moha-carita) should develop mindfulness of breathing. Those with a predominantly faithful temperament (saddha-carita) should recollect the virtues of the Buddha. Vipassana meditation, on the other hand, is suitable for all types of individuals, regardless of temperament.

Samatha meditation can purify the mind only temporarily, but vipassana meditation can permanently purify the mind. Samatha meditation isn’t able to lead its practitioner to the realization of the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, but it can lead to the attainment of mundane supernatural powers (lokiya abhiñña), such as iddhividhi (the ability to perform psychic powers, fly through the air, walk on water, dive into the earth, become invisible and shorten distances), the divine ear, the divine eye, the ability to know the mind of others (cetopariyañana), and the ability to recollect previous lifetimes (pubbenivasanussati-ñana). Although vipassana meditation doesn’t lead to the attainment of such mundane supernatural powers, it can lead its practitioner to the realization of the paths, fruitions and Nirvana.

Whatever the case, in order to realize the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, which is the highest goal in Buddhism, meditators may practice only vipassana meditation without doing any samatha meditation, or they may first practice samatha meditation, aiming for the jhanas, and then practice vipassana meditation using samatha meditation as a foundation, practicing continuously until the realization of the paths, fruitions and Nirvana. But meditators who practice only samatha meditation hoping to realize the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, can’t succeed, like, for example, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta.

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

The most complete principle in the practice of vipassana meditation which appears in the Maha Satipatthana Sutta is the practice of vipassana meditation in accordance with the foundations of mindfulness. This theory, said the Buddha, is the only way for the purification of the mind, for the freedom from suffering and for the realization of the paths, fruitions and Nirvana. This means that in order to purify the mind, reach the end of suffering and realize the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, there isn’t any other way besides practicing in accordance with the theory of the four foundations of mindfulness. The teachings of the Buddha, which can be categorized into up to 84,000 portions (dhammakkhandha), can be reduced down to teachings aiming at purification of the mind.

The literal meaning of the Pali word satipatthana is the dhamma that is a place for the establishment of mindfulness. The practice of the four foundations of mindfulness is using mindfulness to consider or note knowing at every moment of the conditions that arise via the body (kaya), feelings (vedana), mind (citta) and mind-objects (dhamma) or via the five aggregates. This can be divided into four categories.

1. Kayanupassana-satipatthana means to use mindfulness to consider and note knowing the conditions that arise via the body (kaya) or the aggregate of material form (rupakkhandha), like, for example, in walking meditation noting “right stepping, left stepping,” or in noting the in-breaths and the out-breaths and knowing the rise and fall of the abdomen (that is, noting “rising, falling”).

2. Vedananupassana-satipatthana means to use mindfulness to consider and note knowing the conditions that arise via feelings (vedana) or the aggregate of feelings (vedanakkhandha), like, for example, in knowing and noting when a pleasant or unpleasant feeling arises, knowing that one is feeling happy or miserable and what it’s like; or if one is experiencing a neither-pleasant-nor-unpleasant feeling (i.e., feeling neutral), then one’s mind is clear about that.

3. Cittanupassana-satipatthana means to use mindfulness to consider and note knowing the conditions that arise via the mind (citta) or the aggregate of consciousness (viññanakkhandha), like, for example, in knowing and noting the mood of the mind; whether the mind is filled with lust, anger, delusion, sloth, distraction or calm, then know that the mind is in that mood.

4. Dhammanupassana-satipatthana means to use mindfulness to consider and note knowing the conditions that arise via the mind that is the aggregate of perception (saññakkhandha) and the aggregate of mental formations (sankharakkhandha). The aggregate of perception is the ability to remember. The aggregate of mental formations is the thinking. Whenever we think of something, we have to note knowing whatever we are thinking of; or, when a hindrance (nivarana)—satisfaction, dissatisfaction, sleepiness, distraction or doubt—arises, then we have to note knowing that mood.

In summary, the practice of the foundations of mindfulness is just using mindfulness to consider and note knowing at every moment what we are doing as we are doing it, or what we are feeling or thinking. In all cases, we consider only the present moment, not even one second into the past or the future.

The four foundations of mindfulness make up the true heart of the teachings of the Buddha. He repeatedly taught the four foundations of mindfulness to his disciples, from the day of his enlightenment until the day of his passing away (parinibbana). In addition, the Buddha clearly guaranteed the following in the Maha Satipatthana Sutta:

373. ‘‘Ekāyano ayaṃ, bhikkhave, maggo sattānaṃ visuddhiyā, sokaparidevānaṃ samatikkamāya dukkhadomanassānaṃ atthaṅgamāya ñāyassa adhigamāya nibbānassa sacchikiriyāya, yadidaṃ cattāro satipaṭṭhānā.

This is the only way, bhikkhus, for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the destruction of physical and mental suffering, for reaching the right path, for the realization of Nirvana, namely, the four foundations of mindfulness.

The Buddhas and their groups of disciples, both in the past and in the future, all must develop vipassana meditation in order to be able to realize Nirvana:

Yeneva yanti nibbanam buddha tesañca savaka ekayanena maggena satipatthanasaññina.

All the Buddhas and their Arahant disciples have realized Nirvana following the only way, and that way is the four foundations of mindfulness.

The only way is the path on which the Buddhas and their Arahant disciples have walked and consists of the following five characteristics:

It is a path discovered by the Buddha himself alone.

It is a path that exists only in Buddhism.

It is a path that must be individually walked on; no one can walk it for another.

It is a straight path, with no forks in it.

It is a path that leads to only one destination, that is, to Nirvana.

Virtue, Concentration, Wisdom (Sila, Samadhi, Pañña)

Virtue, concentration and wisdom exist both on the mundane (lokiya) level and the supramundane (lokuttara) level. Mundane virtue consists of the 5, 8, 10 and 227 precepts. These precepts make its practitioner into a virtuous person who knows right from wrong, the wholesome from the unwholesome, and the beneficial from the unbeneficial, so that people live peacefully and happily together in a society. Supramundane virtue is the virtue in the practice. It is the virtue of the factors of the path. According to the verse:

Sīlena sugatiṃ yanti, Sīlena bhoga‧sampadā, Sīlena nibbutiṃ yanti

By virtue they go to a happy realm. By virtue is wealth obtained. By virtue they realize Nirvana.

The virtue that leads to a good rebirth and to wealth is mundane virtue. The virtue that leads to the realization of Nirvana is supramundane virtue. Therefore, the mundane and supramundane virtue are different in their practice and yield very different results.

Mundane concentration is the concentration that aims for worldly calm via the practice of samatha meditation going for the jhanas in order to obtain mundane supernatural powers. It leads only as far as the Brahma world. Supramundane concentration is the concentration that aims for a calm that transcends the world, that is freed from the world and leads all the way to Nirvana.

Mundane wisdom. Though you have the wisdom to develop materially, it is only sutamaya-pañña and cintamaya-pañña. It is the wisdom that has been imitated and that belongs to other people. It is the wisdom that is used only to feed your stomach. Supramundane wisdom, on the other hand, is your own wisdom that has arisen from the practice of vipassana meditation; it is called bhavanamaya-pañña. Therefore, we can say that mundane wisdom is the wisdom used to make it in the world, while supramundane wisdom is the wisdom that will free the mind.

***

On one occasion when the Buddha was living at Savatthi, a deity with a question about the Dhamma approached the Buddha and asked him:

‘‘ Antojaṭā bahijaṭā, jaṭāya jaṭitā pajā;

Taṃ taṃ gotama pucchāmi, ko imaṃ vijaṭaye jaṭa ’’ nti.

Ven. Gotama, beings in this world are in turmoil both within and without, being bounded by chaos. How can this turmoil and chaos be cleared up?

The Buddha replied in the Pali:

Sīle patiṭṭhāya naro sapañño, cittaṃ paññañca bhāvayaṃ;

Ātāpī nipako bhikkhu, so imaṃ vijaṭaye jaṭaṃ.

Those established in virtue who practice to give rise to concentration and to the wisdom of vipassana, will be able to clear up the turmoil and chaos in this world.

The turmoil and chaos are the defilements of greed, hatred and delusion that constantly create trouble in our mind. In practice, how can we become established in virtue, developed in concentration and the wisdom of vipassana in accordance with the Buddha’s word? Where is virtue, concentration and wisdom?

In one set of walking meditation or in one set of noting rising and falling, there is the practice of virtue, concentration and wisdom:

The mind that is careful in the rise and fall of the abdomen is virtuous.

The mind that is together with the rise and fall is concentrating.

That which knows the rise and fall is wisdom.

Consequently, virtue, concentration and wisdom exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen.

***

Whenever virtue, concentration and wisdom arise, the eightfold path is also there. Because the eightfold path consists of:

right view (samma-ditthi),

right thoughts (samma-sankappa),

right speech (samma-vaca),

right action (samma-kammanta),

right livelihood (samma-ajiva),

right efforts (samma-vayama),

right mindfulness (samma-sati),

right concentration (samma-samadhi),

where right view and right thoughts make up wisdom; right speech, right action and right livelihood make up virtue; and right efforts, right mindfulness and right concentration make up concentration. Therefore, whenever we practice virtue, concentration and wisdom, it means we are already completely practicing the eightfold path. That is, the eightfold path exists in the rise and fall of the abdomen.

***

How do the three characteristics of existence (tilakkhana) exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen? We know and see how the rise and fall arise, stay for a while and then cease, and then how they arise and cease again, taking turns in this way. This condition is called “impermanence (aniccam).” As we continue noting, feeling arises and we feel pains and aches here and there. This condition is called “suffering (dukkham).” When we note “rise,” we can’t stop it from falling. When feeling arises we can’t prevent it from arising. Whether it be the rising condition or physical pain, we can’t control anything. This condition is called “non-self (anatta).”

Therefore, while we establish mindfulness noting at the body, feelings, mind and mind-objects, the characteristics of impermanence, suffering and non-self intertwine with rupa and nama, which we are always noting. Where rupa and nama arise, the three characteristics of existence are also there. It is like when you see a tiger, you see its stripes as well. That is, the three characteristics of existence exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen.

The Six Fields of Insight (Vipassana Bhumi)

The six fields of insight (vipassana bhumi) are:

the five aggregates (khandha)

the 12 sense bases (ayatana)

the 18 elements (dhatu)

the 22 faculties (indriya)

the four noble truths (ariya-sacca)

the 12 links in the dependent origination (paticca-samuppada)

All these together can be narrowed down to rupa and nama. Therefore, the fields of insight and rupa-nama are one and the same.

There are two ways to learn vipassana meditation:

Learning by levels. This is studying the theoretical principles and doing the practice at the same time. One can study, for example, to know about the six fields of insight and how they consist of the five aggregates, the 12 sense bases, the 18 elements, the 22 faculties, the four noble truths and the 12 links in the dependent origination. This is like a person studying medicine and then treating their own diseases. The diseases then disappear. This method is suitable for those who have a lot of time.

Learning alone. This is practicing and then learning from the experience, which is like treating your own diseases without having studied medicine before. The diseases then disappear all the same. This method is suitable for those who have a little time.

***

Developing vipassana meditation in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness requires that we take the five aggregates as the object of meditation. The five aggregates are material form (rupa), feelings (vedana), perception (sañña), mental formations (sankhara), and consciousness (viññana). Material form is rupa (body). Feelings, perception, mental formations and consciousness make up nama (mind). Therefore, when we narrow down the five aggregates, we have rupa-nama. Making rupa-nama the objects of meditation is the same as making the five aggregates the objects of meditation. Where rupa-nama exist, the five aggregates exist as well.

How do “rising” and “falling” exist in the five aggregates?

The abdomen rising and falling is the aggregate of material form. Feeling happy, miserable or neutral is the aggregate of feelings. Remembering that the abdomen rises and falls is the aggregate of perception. Whether the abdomen rises a lot or a little is the aggregate of mental formations. That which knows the rising and falling is the aggregate of consciousness. Therefore, “rising” and “falling” exist in the five aggregates in this way.

How do “right stepping” and “left stepping” exist in the five aggregates?

The right foot stepping forward and the left foot stepping forward make up the aggregate of material form. Feeling happy, miserable or neutral is the aggregate of feelings. Remembering that the right foot steps forward and the left foot steps forward is the aggregate of perception. When mindfulness notes knowing whether you’re walking slowly or quickly, this is the aggregate of mental formations. That which knows that the right foot is stepping forward and the left foot is stepping forward is the aggregate of consciousness. Therefore, “right stepping” and “left stepping” exist in the five aggregates in this way.

***

There is a very high value attached to “rising” and “falling.” It is like one medicine pill that consists of various kinds of ingredients that are of value. That is, there are various types of goodness found in one place. In addition to virtue, concentration, wisdom and the three characteristics of existence, the 37 requisites of enlightenment (bodhipakkhiya) and the 16 knowledges (ñana) also exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen. The 37 requisites of enlightenment are:

the four foundations of mindfulness (satipatthana)

the four supreme efforts (sammappadhana)

the four bases of psychic power (iddhipada)

the five controlling faculties (indriya)

the five powers (bala)

the seven factors of enlightenment (bojjhanga)

the eight factors of the path (atthangika magga)

All these are contained in the rise and fall of the abdomen.

***

1) How do the four foundations of mindfulness exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen?

Noting “rising” and “falling” is contemplation of the body (kayanupassana-satipatthana). Noting the pains and aches that arise is contemplation of feelings (vedananupassana-satipatthana). Noting the thinking that arises is contemplation of mind (cittanupassana-satipatthana). Noting the five hindrances that arise is contemplation of mind-objects (dhammanupassana-satipatthana). The four foundations of mindfulness, thus, exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen in this way.

***

2) How do the four supreme efforts exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen?

The restraint and care in noting are part of the effort to avoid unwholesome states (samvara-padhana). Defilements cannot arise during the noting because of the effort to abandon unwholesome states (pahana-padhana). The noting and the mind that knows in the practice are part of the effort to develop wholesome states (bhavana-padhana). Guarding the object of meditation with mindfulness so there are no distractions is the effort to maintain wholesome states (anurakkhana-padhana). The four supreme efforts, thus, exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen in this way.

***

3) How do the four bases of psychic power exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen?

Satisfaction in the practice is will (chanda). Perseverance in the practice is energy (viriya). Attention in noting the object of meditation is mind (citta). Consideration of the causes and effects in the noting is investigation (vimamsa). The four bases of psychic power, thus, exist in the rise and fall in this way.

***

4) How do the five controlling faculties exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen? The controlling faculties are influential in the fulfillment of one’s duties. When they undertake their duties in the practice, they will penetrate deeply.

Keeping the mind with rupa and nama, with virtue, concentration and wisdom, with the present moment is the controlling faculty of faith (saddh’indriya). Determining to practice continuously and not talking, not reading, not sleeping a lot, but practicing a lot are part of the controlling faculty of energy (viriy’indriya). Being able to recollect and know before rupa-nama move is the controlling faculty of mindfulness (sat’indriya). Binding the mind so it doesn’t forget rupa-nama and having the mind hold tightly onto its object of meditation are part of the controlling faculty of concentration (samadh’indriya). The wisdom that knows the present moment, that knows rupa-nama, the three characteristics of existence, the wisdom of vipassana, the paths, fruitions and Nirvana is the controlling faculty of wisdom (paññ’indriya). The five controlling faculties, thus, exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen in this way.

***

5) How do the five powers exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen? The five powers are the five types of dhamma endowed with strength.

Confidence in the practice is faith (saddha). Perseverance in the practice is energy (viriya). Recollecting and knowing in the practice is mindfulness (sati). Unwavering determination in the object of meditation being noted is concentration (samadhi). The mind that clearly knows the object of meditation is wisdom (pañña). The five powers, thus, exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen in this way.

***

6) How do the seven factors of enlightenment exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen?

The practice of the four foundations of mindfulness is mindfulness (sati). When mindfulness has arisen, there arises an investigation into the states of dhamma. This is investigation-of-states (dhamma-vicaya). When investigation-of-states has arisen, effort arises. This is energy (viriya). When energy has arisen, delight arises. This is joy (piti). When joy has arisen, tranquility arises. This is tranquility (passaddhi). When tranquility has arisen, determination arises. This is concentration (samadhi). When concentration has arisen, letting go arises. This is equanimity (upekkha). The seven factors of enlightenment, thus, exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen in this way.

Equanimity here is the same as the equanimity in the knowledge of equanimity about formations (sankhar’upekkha-ñana). The state (sabhava) is the same, like the Ping River and the Wang River, where the water is the same but their locations are different.

When the seven factors of enlightenment have arisen, the eightfold path also arises—that is, it has arisen since the start of the practice of virtue, concentration and wisdom, as discussed above. In the practice of the eightfold path, it is said that right view (samma ditthi) is comparable to a train locomotive. The remaining seven factors of the path are like seven railroad cars, one following the other. When the locomotive runs, it will pull the first railroad car with it. The first railroad car will in turn pull the second railroad car. The second railroad car will pull the third, and on it goes until the seventh railroad car. When the train with its seven railroad cars move together at high speed, the cars become one group and they are able to head for the destination together.

The same goes for the eightfold path. Once right view (samma ditthi) arises, the remaining factors from right thoughts (samma sankappa) to right concentration (samma samadhi) also arise. When right concentration has arisen, then right knowledge (samma ñana) also arises. When right knowledge has arisen, right release (samma vimutti) then arises. This is the state (sabhava) in which the defilements have been destroyed by the knowledge of the path (magga-ñana).

In practice, the five knowledges (ñana), that is, the knowledge in conformity (anuloma-ñana), knowledge of change of lineage (gotrabhu-ñana), knowledge of the path (magga-ñana), knowledge of fruition (phala-ñana) and knowledge of reviewing (paccavekkhana-ñana), will arise for a duration of the blink of an eye, one after the other without a break. These five knowledges arise for a very short duration—even a bolt of lightning lasts longer.

When the knowledge of the path arises, it has as its fruit Nirvana, which is a clear understanding of the truth of the cessation of suffering (nirodha-sacca). Once clear understanding in the truth of the cessation of suffering has been obtained, there will also be a clear understanding of the truth of suffering (dukkha-sacca), the truth of the origin of suffering (samudaya-sacca) and the truth of the path leading to the cessation of suffering (magga-sacca), all at the same time.

It’s like when a lamp is lit, the oil dries up and the wick burns. At the same time when light appears, darkness disappears. The lit lamp that dried up the oil is like the knowledge of the path leading to clear understanding of the cessation [of suffering], that is, the drying up of defilements. The wick is like the knowledge of the path that notes knowing in the suffering. The lamp that has dispelled darkness is like the knowledge of the path that has abandoned the origin [of suffering]. The lamp that gives forth light is like the knowledge of the path producing the path [leading to the cessation of suffering].

The clear understanding that arises from the realization of the knowledge of the path is called “ñanadassanavisuddhi,” which is a clear understanding that is pure, into the noble truths (ariya-sacca). It is knowing into the supramundane (lokuttara), or what we call “obtaining the eye of Dhamma.”

How do the 16 knowledges exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen? When mindfulness is brought to note the four dhammas which are body, feelings, mind and mind-objects, there will appear 16 types of characteristics, which are the 16 knowledges (ñana). They will arise in the following order:

knowledge of delimitation of mind and matter (namarupa-pariccheda-ñana) – the knowledge that causes familiarity with rupa-nama

knowledge of discerning cause and condition (paccaya-pariggaha-ñana) – the knowledge that sees the causes of rupa-nama

knowledge of comprehension (sammasana-ñana) – the knowledge that sees the three characteristics of existence (impermanence, suffering and non-self) of rupa-nama

knowledge of arising and ceasing (udaya-bbaya-ñana) – the knowledge that sees the arising and passing away of rupa-nama in accordance with reality

knowledge of dissolution (bhanga-ñana) – the knowledge that sees only cessation

knowledge of fearfulness (bhaya-ñana) – the knowledge that sees rupa-nama as a danger

knowledge of disadvantage (adinava-ñana) – the knowledge that sees rupa-nama as a disadvantage

knowledge of disenchantment (nibbida-ñana) – the knowledge that is bored with possessing rupa-nama

knowledge of desire for deliverance (muñcitukamyata-ñana) – the knowledge that desires to be freed from possessing rupa-nama

knowledge of reflection (patisankhara-ñana) – the knowledge that tries in earnest to be free from possessing rupa-nama

knowledge of equanimity about formations (sankhar’upekkha-ñana) – the knowledge that considers rupa-nama with equanimity

knowledge in conformity (anuloma-ñana) – the knowledge that knows the object of meditation, rupa-nama, for the last time before the realization of the path and fruition

knowledge of change of lineage (gotrabhu-ñana) – the knowledge that cuts the lineage of the worldlings (puthujjana) in order to enter the lineage of the noble ones (ariya-puggala)

knowledge of the path (magga-ñana) – the knowledge that enters the lineage of the noble ones; defilements are destroyed by this knowledge

knowledge of fruition (phala-ñana) – the knowledge that has Nirvana as its object inherited from the knowledge of the path

knowledge of reviewing (paccavekkhana-ñana) – the knowledge that considers the path, fruition and Nirvana that just passed

These 16 knowledges will arise by themselves during the practice. For each knowledge, there will appear characteristics via the mind, arising for the meditator in levels. The 16 knowledges, thus, exist in the rise and fall of the abdomen in this way.

Defilements of Insight (Vipassanukilesa)

While the meditator is practicing on the knowledge of comprehension (sammasana-ñana) or the weak knowledge of arising and ceasing (udaya-bbaya-ñana), one or more defilements of insight (vipassanukilesa) will arise. They will be among the 10 defilements of insight that exist:

Bright light (obhasa). You see bright light appearing like you’ve never seen before, like seeing circular bright lights around your body, some small, some large. Or, you see bright light shining the entire room like the time of midday. Or, there is light being emitted from your body. These are just some examples.

Joy (piti). There are five types, each of which has different characteristics:

Minor joy (khuddaka-piti) has the following characteristics:

coolness, goose bumps all over the body

stiff and heavy body

tears

color white appearing

Momentary joy (khanika-piti) has the following characteristics:

sparks like lightning

stiff body, wavering heart

burning heat over the body

itches like there are insects flying around your body

color red, spotted, appearing

Showering joy (okkantika-piti) has the following characteristics:

swaying body, shaking, sometimes trembling

shaking of the face, hands and feet

saliva in the mouth, nausea, vomiting

like being hit by ripples or waves

colors yellow and light purple appearing

Uplifting joy (ubbega-piti) has the following characteristics:

body feeling taller or lighter, floating.

itches like insects crawling on the face

diarrhea, gastric problems

nodding forwards and backwards

head turning back and forth

mouth opening, closing, biting

body bending forwards and backwards

body fidgeting, lifting up of the hands or feet

colors of pearl, silk-cotton appearing

Pervading joy (pharana-piti) has the following characteristics:

coolness being diffused throughout the whole body

dullness, unwillingness to open eyes or to move

colors indigo-blue, green, emerald appearing

Knowledge (ñana). The feeling arises that you have perfect, proficient knowledge like never before.

Calmness of mind and mental factors (passaddhi). There is a feeling of calm and coolness, both in body and mind, with no distractions and no worries. It is calm and quiet like entering the attainment of fruition (phala-samapatti).

Comfort (sukha). You feel happy, the happiest you have ever been since birth. There is gladness, rejoicing and an unwillingness to leave the practice. You desire to tell of your experiences to another.

Faith (adhimokkha). You feel strong faith in the Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha and the teacher, and a desire to have others come and practice like yourself. There is a desire to repay the debt of gratitude to the center, and a feeling of gratefulness to those who brought you to the practice. You desire to make merits, offer dana, renovate permanent buildings and to seek ordination.

Perseverance (paggaha). You work too hard, practicing in earnest and with determination, fighting to death without giving in, to the extent of being too much.

Mindfulness (upatthana). There is too much mindfulness, so you recollect only the past and the future, abandoning the object of meditation in the present moment.

Letting go (upekkha). There is a feeling of letting go, no happiness, no regrets, no gladness, no displeasure. You are absent-minded and forgetful. You don’t worry and you possess a calm mind, not desiring good or anything else. Whether contacted by a good or bad mood, you still feel neutral. But there is no noting; you allow the mind to follow external objects.

Desire (nikanti). There is satisfaction in the various objects (arammana), such as satisfaction in the bright light, in joy (piti) and in the various signs (nimitta).

These 10 defilements can only arise when the practice of vipassana is being done correctly. Those who have never practiced vipassana meditation will never encounter them. These defilements of insight will never arise for the following four types of people:

those who practice vipassana incorrectly

those lazy in the practice

those who abandon the practice

the noble ones

Some meditators, in delusion, enjoy and delight in the various defilements described here, because the various objects (arammana) all lead to comfort in both the body and the mind in a wondrous way, that is never before experienced. Because of this, meditators stop practicing and don’t continue as they should.

In any case, these meditators will realize that these things that have occurred are all defilements and not the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, nor anything that should be rejoiced at and delighted in, not the path to follow, not what is desired. When this happens, they will abandon their delusion, not rejoicing in those defilements. The pure thought will arise, “That isn’t the way that will give rise to wisdom to see the Dhamma.” This purity is called “maggamaggañanadassanavisuddhi.”

Defilements of insight might arise again in later stages of knowledge (ñana), but in theory they are not considered to be defilements, because there is no desire (nikanti). Though it may happen that they arise, the meditator will not want them, and so they will soon disappear.

Cutting Off the Roots of Vatta (the Cycle of Rebirth)

The roots of vatta (the cycle of rebirth) are the causes why world beings have to cycle in the rounds of birth and death. They are things that block, lure and detain, causing beings to keep cycling. The Buddha pointed out the reason why all the world beings still can’t attain the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, and that is because their mind is still bound to sense-objects (arammana). Therefore, those who will walk the way towards the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, must first cut the roots of vatta.

Khanda means aggregate, or something that is there but is heading for loss—loss of beauty, loss of happiness, loss of certainty and loss of selfness. These four things—beauty, happiness, certainty and selfness—are the roots of vatta by which those who don’t catch on will be lured towards delusion, because they are things that entice the heart. The practice of vipassana in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness is for the sake of destroying the roots of vatta.

Meditators who have practiced contemplation of the body (kayanupassana-satipatthana) will get rid of [the idea of] beauty, that is, the delusion thinking that this or that is beautiful, like, for example, seeing that the body is beautiful and desirable. Once they get a chance to develop vipassana noting the body, by taking “rising, falling” as the object of meditation, the defilement of sense-desire (kama-raga) lessens. The mind will be at peace, free from lust (kama). They won’t even be deluded by the beauty in the sense-spheres, such as the human world and the world of deities (devas). The mind will aim only for Nirvana.

Meditators who have practiced contemplation of feeling (vedananupassana-satipatthana) will get rid of the attachment to happiness, that is, the delusion thinking that this or that is happiness and desiring that happiness forever. Once they get a chance to develop vipassana constantly noting feelings, by taking “pain” or “hurting” as the object of meditation, their mind will become used to nature, which is the state (sabhava) of that feeling. This will make them feel like they can live however, it’s all okay—cold is okay, hot is okay, some pains and aches are okay. The mind, thus, will not become agitated and then suffer accordingly following these sense-objects (arammana). It will see in accordance with reality that things are just the way they are. The mind won’t be stuck in the happiness and will always understand those kinds of states of dhamma (sabhava-dhamma). The mind will only rejoice in the paths, fruitions and Nirvana.

Meditators who have practiced contemplation of the mind (cittanupassana-satipatthana) will get rid of [the idea of] certainty, that is, the delusion thinking that this or that is something certain, and that it will last forever. Once they get a chance to develop vipassana by taking the mind as the object of meditation, they will always see the changes in various kinds of things. One minute we think this way, the next we think in another way, and so it keeps changing. It is uncertain. However the various events in the world may change, the mind that is watching that state (sabhava) will be used to the changes. The mind will be able to catch on to the states of dhamma (sabhava-dhamma). And, thus, it will be able to get rid of the delusion thinking that things are certain. The mind will then delight only in Nirvana.

Meditators who have developed contemplation of mind-objects (dhammanupassana-satipatthana) will get rid of [the idea of] self, that is, the delusion thinking that this or that is self. Up to now world beings all don’t know what the true self is. They can’t ask themselves and can’t answer themselves. They don’t know that this self is just rupa-nama. Once they get a chance to develop vipassana by taking mind-objects as the object of meditation, they will see that beings, individuals and the self don’t exist. Only rupa-nama exist. So they will understand in accordance with reality and won’t be attached to the self. They will catch on to the states of dhamma (sabhava-dhamma). The mind will delight in only Nirvana.

In brief, the development of vipassana in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness will destroy vipallasa-dhamma, which is the wrong view of the four types of real states of dhamma; that is,

The contemplation of body (kayanupassana) will destroy the perversion of seeing the unattractive as attractive (subha-vipallasa-dhamma).

The contemplation of feelings (vedananupassana) will destroy the perversion of seeing what is suffering as happiness (sukha-vipallasa-dhamma).

The contemplation of mind (cittanupassasna) will destroy the perversion of seeing what is impermanent as permanent (nicca-vipallasa-dhamma).

The contemplation of mind-objects (dhammanupassana) will destroy the perversion of seeing what is not-self as the self (atta-vipallasa-dhamma).

Thus, once meditators have developed vipasssana in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness as described here, they will be able to cut the roots of the rounds of rebirth (vatta). They won’t be deluded about the states of dhamma and will be able to see everything in accordance with reality. Their mind will only experience calm and coolness, which is true peace and happiness.

It isn’t always necessary that the meditator be an ordained person in order to practice vipassana for the purification of the mind. Those who aren’t ordained can practice the Dhamma with results as well, because purification of the mind is the truth of life and is something natural, and thus is not restricted by gender, race, class, nationality or religion. When they come to practice, they will all obtain the same results, with the difference being the length of time it takes. It is the same with all the scientific theories, such as the law of gravity. If a person were to throw something up into the air, it doesn’t matter who that person is, where they are throwing it or when, that thing thrown up must always fall back down onto the ground.

Regarding the practice of vipassana meditation, the Buddha had five wishes:

for the purification of the mind.

for the getting rid of sorrow and lamentation.

for the getting rid of physical and mental suffering.

for the attainment of the truth of life.

for the realization of Nirvana.

There are four advantages, said the Buddha, in practicing the Dhamma:

You will be mindful right before dying. You will recollect the merits you have made and the wholesome deed that you have done. They will gather at the mind.

After death, you will take birth in a happy state of existence (sugati), in heaven.

It will become the seed, the foundation, the character, to realize the paths, fruitions and Nirvana in future lives.

If you get the chance to develop vipassana in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness continuously for a period of seven years, you will receive one of two results:

you will become a non-returner (anagami); or

you will become an Arahant in the present life.

Thus, these are the assurances for those who practice the Dhamma.

Important Principles in the Practice

There are four important principles in the practice of vipassana in accordance with the four foundations of mindfulness.

1. You have to note the conditions in the present moment (paccuppanna-dhamma). Whether you note “rising, falling” or “right stepping, left stepping,” you have to note them in the present moment.

The mind that notes “rising” and the rising of the abdomen must be simultaneous. Don’t let one be before or after the other.

The mind that notes “falling” and the falling of the abdomen must be simultaneous. Don’t let one be before or after the other.

When we note “right” we must lift our right foot up immediately.

When we note “step” we must move our foot forward immediately.

When we note “-ing” we must place our foot on the ground simultaneously.

We practice in the same way for the left foot as the right foot.

2. We must practice continuously. After doing the mindful (satipatthana) prostration, we have to walk and sit meditation according to the time schedule we have fixed for ourselves, so that the three activities are continuous. While resting, we must try to note the minor bodily activities as well, for example, when we wash our face, take a shower, eat, urinate or defecate, stretch or bend our arm. Even when we’re going to bed, we have to note “lying (down), lying (down)” and then note “rising, falling” until we fall asleep.

Satipatthana prostration is a way to gather the mind (mindfulness) at the hands.

Walking meditation is a way to gather the mind (mindfulness) at the foot.

Sitting meditation is a way to gather the mind (mindfulness) at the abdomen and at the various touching points.

3. The practice must consist of [the following] three good qualities:

Energy (atapi): perseverance and earnestness; doing it seriously.

Mindfulness (satima): mindfulness that recollects and knows the rupa and nama that arise.

Clear comprehension (sampajano): mindfulness that follows and notes knowing the rupa and nama at all times. It is like a person who rocks a cradle; their eyesight must follow the rope of the cradle at all times.

4. The five controlling faculties (indriya) and powers (bala) must be balanced:

Faith (saddha) must be balanced with wisdom (pañña).

Effort (viriya) must be balanced with concentration (samadhi).

Mindfulness (sati) is the supervisor. The more we have of this mindfulness, the better it will be.

If faith is great but wisdom is weak, greed (lobha) will take control.

If wisdom is great but faith is weak, doubt (vicikiccha) will take control.

If energy is great but concentration is weak, distraction (uddhacca) will take control.

If concentration is great, but energy is weak, laziness (kosajja) will take control.

Whether the practice produces quick or slow results depends on your ability to balance the controlling faculties and powers stated here.

To increase faith: Establish your mind at rupa-nama, virtue (sila), concentration (samadhi), wisdom (pañña) and the present moment.

To increase energy: Persevere and earnestly do the practice. Eat little, sleep little, talk little, but practice a lot.

To increase mindfulness: Recollect and know rupa-nama and note the conditions all the time.

To increase concentration: Pay firm attention to the object of meditation that is being noted. No matter what the object of meditation the mind is noting, have the mind firmly note in that object of meditation. No matter what condition the mind has slipped into, have the mind note knowing in that condition.

To increase wisdom: Know rupa-nama, the present moment, the three characteristics of existence (tilakkhana), the wisdom of insight (vipassana-pañña), the paths, fruitions and Nirvana.

Why must there be so much emphasis on the present moment? Because if we don’t note the conditions in the present moment, the practice won’t yield results, for momentary concentration (khanika-samadhi) won’t be able to gather itself. But if the noting is done in the present moment, momentary concentration will gather itself well, and the controlling faculties (indriya) and powers (bala), which are faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration and wisdom, will increase in great strength. It is like a knife that is well-sharpened; it becomes useful.

Noting in the present moment is like the cat that is catching mice.If the mouse hasn’t arrived and the cat tries to catch it, the cat won’t get the mouse, for it is going into the future. If the mouse has already gone, and the cat tries to catch it, the cat won’t get the mouse, for it has become the past. If the mouse arrives and the cat happens to try and catch it at this time, the cat will get the mouse, for it is in the present moment.

Therefore, the present moment is something important. Noting in the present moment causes momentary concentration to gather itself. Once momentary concentration has gathered itself, the controlling faculties and the powers gain great strength. Once the controlling faculties and the powers possess great strength, they will automatically perform the duty of destroying the defilements (kilesa) in the knowledge of the path (magga-ñana), which is the 14th knowledge, without requiring any of our interference. We only have to practice correctly, in accordance with the principles that have been laid down. This is like rice farmers who are responsible for loosening the soil, giving fertilizer, draining water into the fields, and then planting the rice seedlings in accordance with the principles of correct farming. They don’t need to think about when the rice will form ears; when the time comes, they will form ears on their own.

What importance is there in noting? Noting is an important core in the practice of vipassana. It is the job of mindfulness that it must follow and keep noting, follow and keep knowing, at all times. It is the way to cut the states of dhamma. Noting continuously makes concentration grow strong and closes the leaking holes to prevent evil from flowing into the mind. We will be able to see the rising and ceasing of rupa-nama at all times and to clearly see the three characteristics of existence. Therefore, we must at all times keep noting the objects that arise via the body, feelings, mind and mind-objects. If life is going to have value, it will be when we note knowing the conditions.

The benefits of the form “-ing” are threefold:

It is one way to strengthen momentary concentration (khanika-samadhi) so that it has energy.

It divides rupa and nama so they become disconnected, with a gap, in order to be able to clearly see rupa-nama.

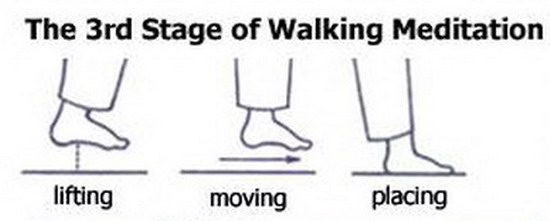

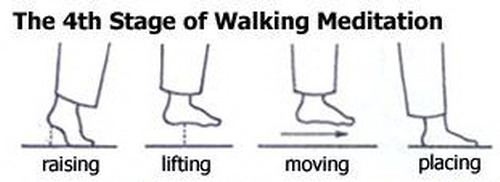

It is so that we can more clearly see impermanence (aniccam), suffering (dukkham) and non-self (anatta). From part 3 of the Commentary to the Visuddhimagga, it is stated on page 251, lines 5-6, that walking meditation can be divided into 6 stages: raising (uddharana), lifting (atiharana), moving (vitiharana), lowering (vossajjana), touching (sannikhebhana), and pressing (sannirumbhana).

The Buddha pointed out five benefits to walking meditation:

endurance in walking long distances;

endurance in the practice;

helps digest food;

helps to drive out wind-related illnesses from the body; and

improves concentration (the concentration obtained from walking meditation will last long).

The Three Characteristics of Existence (Tilakkhana)

The three characteristics of existence are three equal marks. All world beings including us are subject to the law of the three characteristics of existence, which are impermanence (aniccam), suffering that is hard to endure (dukkham) and the state of not being under anyone’s control (anatta).

Where are the three characteristics of existence? The three characteristics of existence exist at rupa-nama, being intertwined with the rupa-nama which we are constantly noting. Where rupa-nama are, the three characteristics are also there. It’s like if you see a tiger, you also see its stripes.

The importance of the three characteristics of existence. The aim of the practice of vipassana is to disentangle the three outstanding marks of impermanence, suffering and non-self, so that they become clear to the mind, that is, so that they are clearly understood by the meditator. Once there is clear understanding you will be able to see that everything in this world without exception is impermanent, suffering and non-self. The mind won’t be encouraged and it will desire to let go of the desire to have and to own. It will desire to withdraw.

Therefore, the three characteristics are like a magnifying glass of dhamma that will focus and enlarge what we see, giving rise to boredom within us, reducing lust and lessening grasping in all beings. The mind will be calm and cool, peaceful and happy. It will make us see the truth that craving (tanha) is the cause of suffering.

There are three dhammas that obscure the three characteristics of existence:

- Continuity (santati) – obscures impermanence (aniccam); it is the dhamma that obscures rupa-nama, making us see them to be permanent (niccam).

- Body postures (ariyapatha) – obscure suffering (dukkham). Every body posture, whether it be sitting, lying down, standing, or walking, all consists of suffering. Because of the obscurity caused by the changing of postures, however, we don’t see the suffering. So we say body postures obscure suffering.

- Solidity (ghana-sañña) – obscures selflessness (anatta), so we see them as beings, individuals, the self, us and them; this gives rise to attractive and desirable sense-objects (arammana). If we were to take them apart, they are [actually] something dirty, rotten and decayed. Thus, in this way, we say ghana-sañña obscures selflessness.

The three characteristics that will give rise to the knowledge of insight (vipassana-ñana) must be the three characteristics that come from objects of meditation that are part of ultimate reality (paramattha-arammana), and not from objects of meditation that are part of conceptual reality (paññatti-arammana). In other words, when you clearly see that rupa-nama and the five aggregates are impermanent, suffering and non-self, that is, there are no beings, individuals or a self, but only states (sabhava) that know and states that are known, then they become the three characteristics that will give rise to knowledge of insight.

In order to develop vipassana so that it will give rise to the wisdom to see the three characteristics of existence, you have to concentrate on rupa-nama as objects of meditation in the present moment, that is, when rupa-nama are arising and ceasing. Once concentration has gathered itself well, the mind that once liked to struggle and waver in the various objects, will become calm, stilled and stable in the object that is being noted. We will know and see things that we have never known nor seen before. While we are noting, we will be satisfied that we have known and seen the reality that there are only rupa-nama that take turn working as a pair.

Contemplation of impermanence (aniccanupassana). When the noting is done more clearly, you will see that not even one of the objects of meditation that has been noted, is at all stable. You will only always see the impermanence of that object of meditation. When you note the object that has arisen, that object then ceases right away, and a new object comes to take its place. They switch back and forth. The clear understanding that arises from the knowledge (ñana) while we are noting that rupa-nama are impermanent is called “aniccanupassana.”

Contemplation of suffering (dukkhanupassana). Once there is clear understanding into the impermanence of rupa-nama, the unpleasant feeling (dukkha-vedana) that arises from aches, pains and numbness, will come in to interfere and disturb the mind, destroying the calm and stability that exist then. The clear understanding that arises from the fight with feelings by being unwilling to change postures until you are able to finally overcome that feeling is called “dukkhanupassana.”

Contemplation of non-self (anattanupassana). While you are noting the condition, whether it be the arising and ceasing of rupa-nama, or the suffering and torture arising from feelings, you see that it is not under anyone’s control. It is as it is in accordance with the states of dhamma (sabhava-dhamma). The clear understanding of this kind of truth is called “anattanupassana.”

Therefore, the three characteristics are true vipassana. Once you have developed vipassana until wisdom arises, and you see the three characteristics in this way, the wisdom then starts to inch slowly towards the paths, fruitions and Nirvana.

Entering into the Knowledge of the Path (Magga-Ñana)

In the practice, in order to enter the knowledge of the path (magga-ñana), we have to do so via one of the characteristics of existence, that is, via the sign of impermanence (aniccam), suffering (dukkham) or non-self (anatta).

If the rise and fall of the abdomen increase in speed, this indicates the impermanence of rupa-nama. When the mind ceases during this time, then [the meditator] enters the knowledge of the path via the sign of impermanence. This is called the “signless path (animitta-magga).”

If the rise and fall of the abdomen are not even, and the meditator feels uncomfortable, having to encounter strong feelings (vedana), this indicates the suffering of rupa-nama. When the mind ceases during this time, then [the meditator] enters the knowledge of the path via the sign of suffering. This is called the “desireless path (appanihita-magga).”

If the rise and fall of the abdomen become lighter and finer, this indicates the selflessness of rupa-nama. When the mind ceases during this time, then [the meditator] enters the knowledge of the path via the sign of non-self. This is called the “emptiness path (suññata-magga).”

The realization of the paths, fruitions and Nirvana can only occur via one of these three conditions. The reason that meditators enter the knowledge of the path via different conditions, is because they have accumulated the perfections (parami) differently. That is, those who have previously offered dana and kept precepts will enter the knowledge of the path via the condition of impermanence. Those who have previously practiced samatha (calm) meditation will enter the knowledge of the path via the condition of suffering. Those who have previously practiced vipassana (insight) meditation will enter the knowledge of the path via the condition of non-self.

In any case, the practice of vipassana meditation can be divided into four stages. The knowledges (ñana) that belong to each stage are known by the same name but they differ in their degree of coarseness and fineness. And the knowledge of the path (magga-ñana) belonging to each stage are different in their power to destroy defilements (kilesa). That is, the knowledge of the path (magga-ñana) that arises in the first stage of the practice is called the “knowledge of the path of stream-entry (sotapatti-magga-ñana).” It functions to completely destroy defilements that are very coarse. The knowledge of the path (magga-ñana) that arises in the second stage of the practice is called the “knowledge of the path of once-returning (sakadagami-magga-ñana).” It functions to completely destroy defilements that are slightly coarse. The knowledge of the path (magga-ñana) that arises in the third stage of the practice is called the “knowledge of the path of non-returning (anagami-magga-ñana).” It functions to completely destroy defilements that are the least coarse. The knowledge of the path (magga-ñana) that arises in the fourth stage of the practice is called the “knowledge of the path of Arahantship (arahatta-magga-ñana).” It functions to completely destroy the fine defilements that remain.

Defilements that are Responsible for the Impurity of the Human Mind

The defilements that bind world beings to the vatta (the cycle of rebirth) are called “fetters (samyojana),” of which there are ten:

- identity view (sakkaya-ditthi): the holding-on to a self

- doubt (vicikiccha): doubt in, for example, the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha

- clinging to rules and rituals (silabbata-paramasa): wrong practice of customs

- sensual desire (kama-raga): delight in forms, sounds, smells, tastes, touch and mind-objects

- ill will (patigha): anger

- desire for fine-material existence (rupa-raga): delight in the rupajjhanas

- desire for immaterial existence (arupa-raga): delight in the arupajjhanas

- conceit (mana): pride

- restlessness (uddhacca): distraction

- ignorance (avijja): the inability to understand clearly

The Mind of the Noble Ones

The Mind of a Stream-Enterer (Sotapanna)

For those who have realized the initial stage of the paths and fruitions, that is, for those who are stream-enterers (sotapanna), three fetters have been completely destroyed:

- identity view (sakkaya-ditthi): the holding-on to a self

- doubt (vicikiccha): doubt in, for example, the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha

- clinging to rules and rituals (silabbata-paramasa): wrong practice in customs

In addition, they are not stingy, jealous, deludingly conceited, despising, deceitful or prejudiced. They are pure in the five precepts. This is the purity of the mind of a stream-enterer. Though it is purity in its initial stage, but it is a high form of purity, as it elevates the person to a position that is higher than ordinary people. And, thus, they are called a noble one (ariya-puggala).

There are three types of stream-enterers:

- If the controlling faculties (indriya) are strong, then they are the Single-Seed (ekabiji), and will be reborn only one more time.

- If the controlling faculties are moderate, then they are the Clan-to-Clan (kolankola), and will be reborn only 2-3 more times.

- If the controlling faculties are weak, then they are the Seven-Times-At-Most (sattakkhattu-parama), and will be reborn only seven more times at most.

Furthermore, according to the Buddhist doctrine, those who have practiced passed the second knowledge, which is the knowledge of discerning cause and condition (paccaya-pariggaha-ñana), are called junior stream-enterers (cula-sotapanna). At the time of death, if the knowledge hasn’t degenerated, they won’t fall into a miserable realm of existence (apaya), but will take birth in a happy realm (sugati), in heaven. But the third life is uncertain; it is possible [for them] to fall into a state of woe then. To be [permanently] free from the state of woes, they would have to keep practicing vipassana meditation until they realize the noble paths (ariya-magga) and fruitions (ariya-phala).

The Mind of a Once-Returner (Sakadagami)

The mind of those who have practiced vipassana meditation until they realize the middle stage of the paths and fruitions, that is, the mind of once-returners (sakadagami), is more pure than the mind of stream-enterers. That is:

- Identity view (sakkaya-ditthi) has been permanently abandoned.

- Doubt (vicikiccha) has been permanently abandoned.

- Clinging to rules and rituals (silabbata-paramasa) has been permanently abandoned.

- Sensual desire (kama-raga) in its coarse form has been abandoned.

- Ill will (patigha) in its coarse form has been abandoned.

And they won’t speak maliciously or curse in a harsh way. According to the Buddhist doctrine, once-returners will be reborn only once more until they realize the paths, fruitions and Nirvana.

The Mind of a Non-Returner (Anagami)

The mind of those who have practiced vipassana meditation until they realize the high stage of the paths and fruitions, that is, the mind of non-returners (anagami), is ever more pure.

- no identity view (sakkaya-ditthi);

- no doubt (vicikiccha);

- no clinging to rules and rituals (silabbata-paramasa);

- no sensual desire (kama-raga);

- no ill will (patigha).

But there are still five fine defilements left, which are:

- desire for fine-material existence (rupa-raga);

- desire for immaterial existence (arupa-raga);

- conceit in accordance with reality (mana);

- distraction (uddhacca);

- a lack of clear understanding (avijja), that is, a lack of clear and perfect understanding of the truth of life and of all things.

According to the Buddhist doctrine, [for such people] this life is the last life [on earth]. Once they have left the world, they will be reborn in the Pure Abodes (suddhavasa) in the Brahma world, which is free from lust (raga), and will realize Arahantship in that existence.

The Mind of an Arahant

For those who have practiced vipassana meditation until they realize the highest stage of the paths and fruitions, that is, for those who are Arahants, the five fine fetters that remain in the mind of a non-returner, permanently cease without remainder. Even though they are still living in the world, their mind is pure and free from all defilements—no greed (lobha), no hatred (dosa), no delusion (moha), no craving (tanha), no clinging (upadana). Only the five aggregates remain.

If they are lay people, they would have to ordain to become a monk on the same day (or within seven days according to some scriptures) of their realization of Arahantship. Otherwise, their aggregates would have to cease (parinibbana) on that day. This is because the life of an Arahant is very pure and isn’t suitable for the lay status; they can only live in the ordained status. At the ceasing of their aggregates, noble ones in the highest stage of enlightenment will enter Nirvana, freed from birth, old age, sickness and death—the end of suffering, the end of birth (jati), the end of becoming (bhava). They don’t have to return to cycle in the rounds of birth and death ever again.

***

Quite a few people misunderstand that those who have realized the paths, fruitions and Nirvana, must not have any more greed, hatred and delusion, and must turn to the religious life alone. And sometimes people think that they must live in solitude with no involvement with their children and spouse or any kinds of business. The truth is those who have realized the initial stage of the paths and fruitions and became stream-enterers, although they are noble ones with a mind that is very much higher than ordinary people, but they still have greed, hatred and delusion. But these are the finer types of greed, hatred and delusion, as the coarse types have been destroyed. There are still parts of greed, hatred and delusion left in accordance with the stage of enlightenment of that noble one. These will be completely destroyed only when they become an Arahant.

Relationship with Family

Stream-enterers still have family relationships but in a way that is more calm and careful than before, because their mind has become more purified. Even if they realize the paths and fruitions of non-returning, in which sensual desire has been completely destroyed and there are no sexual relationships, but family stability would not change. This is because objects of sexual enjoyment (kamarammana) need not always be at the forefront of families. As for doing businesses and other work, stream-enterers and once-returners will probably continue on with that, but in a way that will be better than before for sure, because they will work with a mind that has become cleaner and more pure. But non-returners, whose sensual desire has been completely destroyed, might not be interested in running a business but will probably be more likely to carry out their duties in the religion that are beneficial to the human race. If they have realized Arahantship, then it is certain that they absolutely won’t become involved with the world, because they must live the simple life by nature until their aggregates cease, realizing parinibbana.

Regarding Sorrow

Some people think that noble ones probably do not grieve or weep when they are separated from the beloved. But in truth noble ones in the lower stages of enlightenment still sorrow, though less than ordinary people. That is, stream-enterers may still cry at the loss of what is most dear to them; like when Ven. Ananda knew about the passing away (parinibbana) of the Buddha, he cried, because he was still a stream-enterer.

Once-returners have little sorrow. Non-returners don’t sorrow at the loss of what is dear, because sensual desire has been completely destroyed. Arahants are not moved by anything, whether it be sorrow, trouble, irritations or disturbances. These won’t arise in them at all.

Practicing the Dhamma in the Higher Stages

When meditators have realized the path and fruition of stream-entry and wish to continue the practice of vipassana in order to realize the second path and fruition of once-returning (i.e., sakadagami-magga and sakadagami-phala) so that their mind becomes further purified, they should stop resolving to enter the attainment of fruition (phala-samapatti).

Pay homage to the Triple Gem with flowers, incense sticks and candles, and resolve, “I am practicing vipassana in order to realize the path and fruition of once-returning.” Then start meditating by walking meditation in the 6th stage for one hour and then sit meditation noting “rising, falling” [of the abdomen] for one hour, switching back and forth like how it has been practiced before.

Interesting Points